It seems like the interest in vampires and their role in popular culture returns cyclically. There was a recent Op Ed piece in the New York Times about the current popularity of vampires and their history written by Guillermo del Toro and Chuck Hogan that is well worth reading.

I actually read Dracula for the first time just a few years ago and was surprised and delighted both by the style of the novel and the characterizations. The Count is suave but as a vampire he does not seem at all sensual which seems to be an innovation of the films or a return to the Polidori story. He is more often described as a sated, fattened tick. If anything Dracula seems more like commentary on old fattened ruling classes being thwarted by a rising middle class (a doctor, a lawyer, a professor and a clever woman). However, there are also in the novel the women, first those Harker encounters while staying with the Count, and then Lucy, they do seem both sensual and dangerous, and no doubt an argument could be made about the threat of women's changing social roles in Dracula but I have already digressed far enough.

In Neverwhere, the Velvets, particularly Lamia, have more in common with these women than the new vampire craze. It is also ambiguous whether they are vampires in the traditional sense at all since Lamia speaks of being cold and it is more the stealing of warmth, breath and life rather than blood. They are more reflective of a temptation, a desire to be flattered and any good hero has to face temptation. This is why Richard is easily beguiled both by his willingness to still expect good from others and by the temptation to feel like he is capable and has some measure of control, especially after having gone through the ordeal and having been so lost in London below. He wants to assert himself and a Lamia makes him feel like that is possible. Alternately, it does not seem like they are intrinsically evil, they are more like alluring carnivorous plants that are designed to attract what they need to live but that it has as much to do with the victim as the victimizer.

Since I can't resist thinking about names, Lamia is a minor demigod in Greek mythology with a tangled story. One of many of Zeus's seductions her children were taken by an angry Hera and she went mad and began killing (ore eating) other children. As punishment she was turned into a snake (or a half-snake and in some versions)and cursed with second sight but unable to close her eyes. Among her children are the monster Scylla but sometimes other monsters as well.

In Neverwhere, the Velvets, particularly Lamia, have more in common with these women than the new vampire craze. It is also ambiguous whether they are vampires in the traditional sense at all since Lamia speaks of being cold and it is more the stealing of warmth, breath and life rather than blood. They are more reflective of a temptation, a desire to be flattered and any good hero has to face temptation. This is why Richard is easily beguiled both by his willingness to still expect good from others and by the temptation to feel like he is capable and has some measure of control, especially after having gone through the ordeal and having been so lost in London below. He wants to assert himself and a Lamia makes him feel like that is possible. Alternately, it does not seem like they are intrinsically evil, they are more like alluring carnivorous plants that are designed to attract what they need to live but that it has as much to do with the victim as the victimizer.

Since I can't resist thinking about names, Lamia is a minor demigod in Greek mythology with a tangled story. One of many of Zeus's seductions her children were taken by an angry Hera and she went mad and began killing (ore eating) other children. As punishment she was turned into a snake (or a half-snake and in some versions)and cursed with second sight but unable to close her eyes. Among her children are the monster Scylla but sometimes other monsters as well.

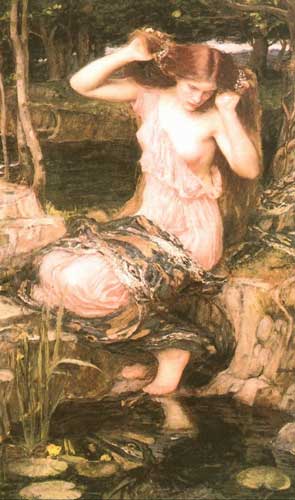

She was a popular subject for the Preraphaelite painters (see the paintings by Herbert Draper above and John William Waterhouse to the left) and she makes an appearance as a snake turned into a human woman in a poem Lamia by John Keats, although in this case a young man falls in love with a snake who has been turned into a woman and is stricken when he discovers her true identity.

Later the name was made plural, Lamiae, and they become more of a type of female witch, vampire or succubus and work their way into folk tales often as a dangerous person a hero must encounter for information but overcome.

There may be an interesting Anglo-Saxon counterpoint in Grendel's Mother, who attacks after the death of Grendel and must be overcome by the hero Beowulf and by that account the any powerful or sensual women with ambiguous motives in Arthurian legends would fit as well.

The name Velvets for the group, type of creature that they are, is very evocative. I admit the first time I heard it the Byron poem popped into my head, "She walks in beauty like the night. . ."

I would hate to minimize Lamia in Neverwhere to a mere type. The complexity and variety of these representations means the actress playing Lamia will have a lot of room for interpretation. Interestingly, the production has double casting so the same actress will be playing both Jessica and Lamia which will allow for some interesting resonances in thinking about Richard's relationship to women.